From Mahishasura to Banasura

A struggle for the visibility

Almost every mountain and hill touched by Indian civilization has a mythical story associated with it. Most of the time, these stories helped conserve local biodiversity by making the mountains sacred. However, in some cases, the worship of these mountains has gone to extremes, with the stories of gods taking precedence over the original intent of conservation.

Out of all these mountains, our focus is on Chamundi Betta in Mysore and Banasura Peak in Wayanad, both located in southern India. The Chamundi Betta has a story of the goddess leader Cāmuṇḍi defeating Mahiṣāsura, a tyrannical king of Mysore, and restoring order. The name Mysore is derived from mahiṣa-ūru — the city of Mahiṣa.

The Banasura Peak is named after Bāṇāsura, the son of Mahābali — a celebrated king who was removed from Earth and sent to the underworld pātāla by the gods when he grew too powerful and threatened their rule.

The Geography

The Banasura Peak (2073m) forms part of the Western Ghats mountain chain, which runs parallel to the west coast of the Indian Peninsula. It is the northernmost peak above 2000m between the Himalayas and the Nilgiris. In contrast, Chamundi Hill is an isolated hillock located in the plains of the Deccan Plateau. Its elevation is modest, averaging 1060m, rising approximately 300m above the surrounding plains of Mysore city.

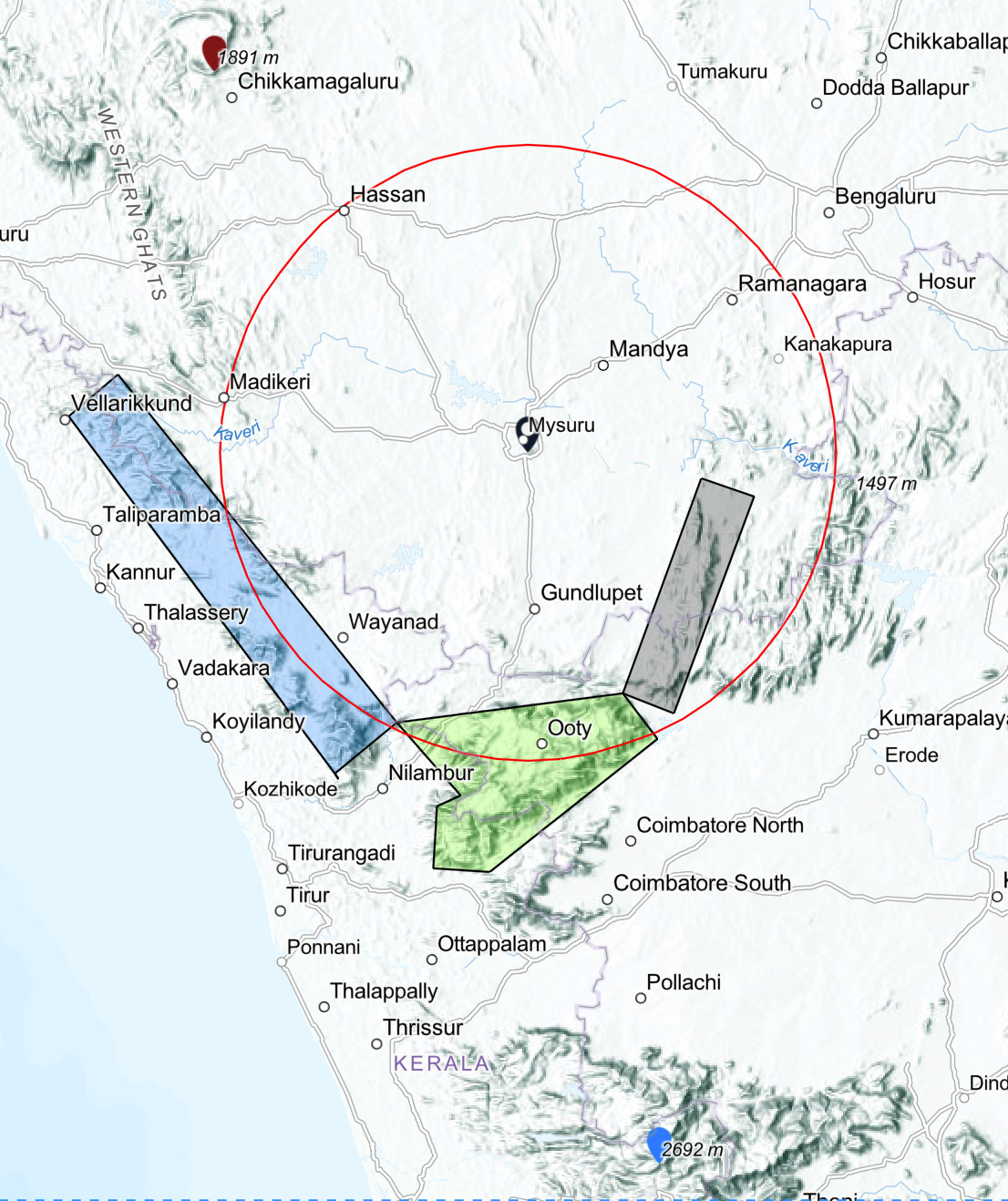

The city of Mysore is located nearly equidistant from several notable mountain ranges in South India:

The Western Ghats of Coorg and Kerala

The Eastern Ghats of Chamarajanagara - specifically Biligiriranga range

The Nilgiris, where these two mountain chains meet

All of these mountain chains are located within a distance of around 100km from Mysore. While this makes for easy weekend trips, it has more interesting implications given that the limit of clear-air visibility is around 200km1.

Visibility and Luck

With no polluting particles in the atmosphere, visibility would be at its maximum. However, modern industrial civilization seldom allows this to happen. The atmosphere is often filled with particulate matter, oxides of sulfur, and dust particles of varying sizes. All of these contribute to the scattering of light, thereby reducing visibility. On an average winter day, visibility can be less than 30 km.

The arrival of the monsoon changes everything. Strong winds and rains help wash these particles out of the atmosphere, improving air quality. Even the rain-shadow areas of the Deccan Plateau benefit from this, while the Western Ghats are often covered with clouds and rain. During the "Monsoon Break" phase, when the rains subside, the mountains are still often shrouded in mist.

This is where luck comes into play—on extremely rare occasions during the break phase, the high mountains are not covered in clouds, and the plains experience less pollution. It turns out I was a bit lucky when I visited Mysore in late September of 2024.

The Lucky Evening

It was a break monsoon day. The weakened westerly winds had pushed moisture further inland, causing thunderstorms and showers over the plains. That evening, from Chamundi Betta, one side of the city was completely covered by pitch-black clouds pouring rain, while the other side had already cleared after the rain. The sun, setting behind the dark clouds, cast a surreal magenta hue over the entire environment, creating a scene both dramatic and confusing.

Neelgiris of Tamil Naadu

And it was the time for action for the 250mm crop-frame lens! Out in the distant sky to the south, I could barely distinguish the cloud bottoms from the peaks of Neelgiris (>2000m, ~100km Line of Sight distance).

Turning slightly to the southwest revealed more of the foothills and the rugged peaks beyond.

I'm not a first-time observer of the Neelgiris from Mysore. One of my friends captured a stunning shot of the Neelgiris during the COVID lockdowns, at the start of the monsoon. The air was much clearer back then than it is now!

Banasura and Cousins

The western horizon would have been completely dominated by the peaks of the Western Ghats of Kerala — as suggested by Peakfinder. However, all I could see were clouds and a red sky. While I could have called seeing the Neelgiris a success and given up on the rest, I decided to give luck a try and shot aimlessly where Peakfinder indicated the peaks should be. And voila — during post-processing, Banasura (2073m, 105km LOS distance) revealed its peak above the clouds!

Where I was supposed to see the peaks of Chembara (2100m, 106km LOS distance) further south, I instead saw its foothills, located within the Bandipura Forest.

To Coorg

While post-processing, I noticed a mysterious line within the clouds, which turned out to be a mountain — the Brahmagiri of Irpu (1608m, 83km LOS distance), where the River Lakshmanateertha originates. This mountain should not be confused with the Brahmagiri of Bhagamandala, also located in Coorg, where the River Kaveri originates.

More Western Ghats

While I was supposed to see the Bettadapura Hills (1318m, 64km LOS distance) of the plains, with Kote Betta (1635m, 104km LOS distance) of Somawarapete in the background, the view was obscured by clouds and rain. Theoretically, Kumara Parvata (1712m, 115km LOS distance) and even the Chandradrona Range of Chikkamagaluru (>1800m, 161km LOS distance) could also be visible. According to folklore, a light lit at Devirammana Betta in the Chandradrona Range, visible from Chamundi Betta, once signaled the start of Deepavali celebrations. Seeing such a sight in modern times would be nothing short of a miracle!

The Eastern Mountains

While the western horizon was vibrant with colors, the eastern horizon appeared dull and was slowly preparing for nightfall. However, squinting at the seemingly blank horizon revealed the Biligiriranga Range of the Eastern Ghats (>1200m, ~75km LOS distance).

While more mountains could have been visible under better conditions, it was getting dark and rainy, so I had to stop for the day, satisfied with the gems I had collected.

The Previous Day

Good visibility conditions had prevailed the previous day as well. From a rooftop, I could see the hillocks all around. I also aimed my camera in the general direction of the Neelgiris, as suggested by Peakfinder, but ended up with a partly failed attempt.

There were small hillocks scattered all around.

Moral of the Story

As someone who lives in the mountains, the plains with no mountains in sight often feel dull. However, the plains of the Deccan Plateau in India are dotted with small hills, and given the right conditions in both space and time, one can also catch glimpses of nearby mountain chains.

If you want to imagine and understand what mountains you can see from a given place, Peakfinder2 is an extremely useful tool, and their mobile app is especially handy when you're on location. It not only helps visualize what’s around but also makes us realize the serious impacts of pollution on visibility, making us wonder what other effects it might have on human society and health.

While we can see the hills and mountains in these photos, they would benefit from removing the dust spots on the lens and performing color corrections to address the artifacts caused by dehazing. I hope to capture the mountains more clearly next time, with better conditions both in terms of space and time, requiring less dehazing!

As a mysurian, I was never think or knew about the visibility of nilgiris, western ghats, Coorg etc.. but after reading this post I found very happy inside and we will definitely search for this mountains whenever we visit Chamundi hills.

Thanks to Vinayaka for this beautiful post.